Enter the Mind Palace: Reasoning and Planning for Long-term Active Embodied Question Answering

Abstract

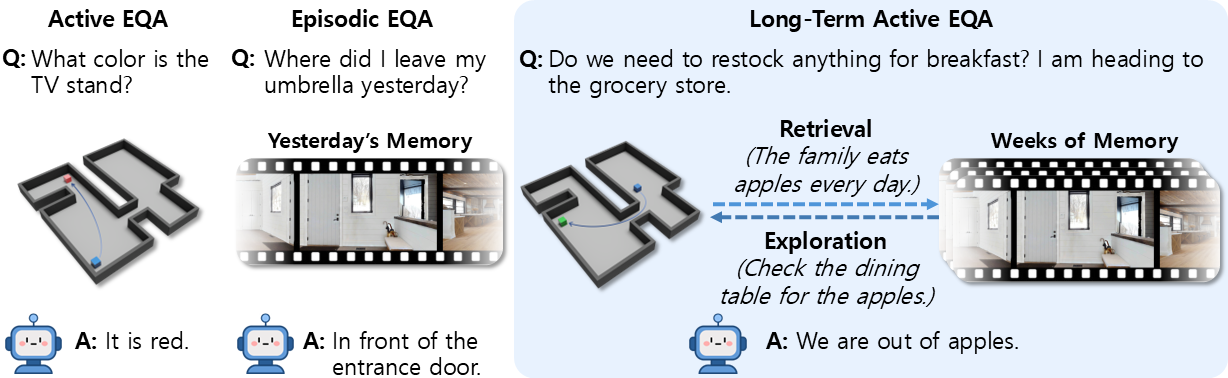

As robots become increasingly capable of operating over extended periods—spanning days, weeks, and even months—they are expected to accumulate knowledge of their environments and leverage this experience to assist humans more effectively. This paper studies the problem of Long-term Active Embodied Question Answering (LA-EQA), a new task in which a robot must both recall past experiences and actively explore its environment to answer complex, temporally-grounded questions. Unlike traditional EQA settings, which typically focus either on understanding the present environment alone or on recalling a single past observation, LA-EQA challenges an agent to reason over past, present, and possible future states, deciding when to explore, when to consult its memory, and when to stop gathering observations and provide a final answer. Standard EQA approaches based on large models struggle in this setting due to limited context windows, absence of persistent memory, and an inability to combine memory recall with active exploration.

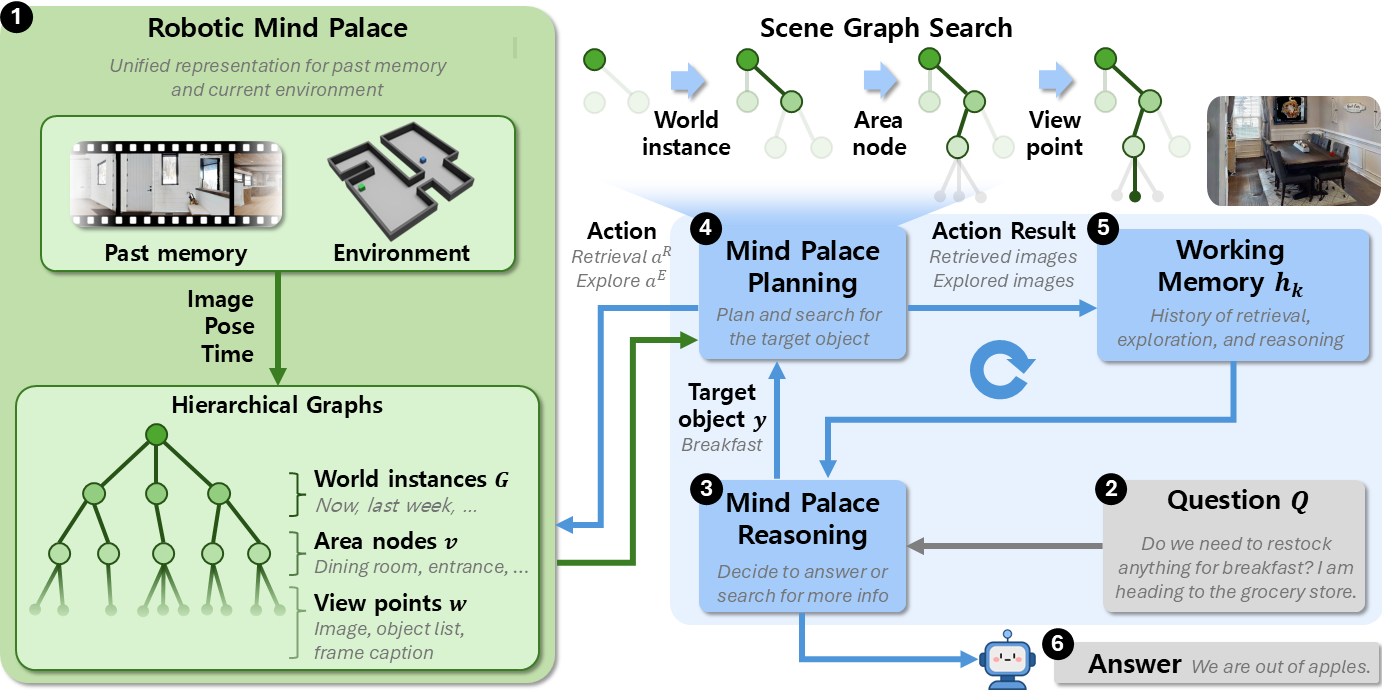

To address this, we propose a structured memory system for robots, inspired by the mind palace method from cognitive science. Our method encodes episodic experiences as scene-graph-based world instances, forming a reasoning and planning algorithm that enables targeted memory retrieval and guided navigation. To balance the exploration-recall trade-off, we introduce value-of-information-based stopping criteria that determine when the agent has gathered sufficient information. We evaluate our method on real-world experiments and introduce a new benchmark that spans popular simulation environments and actual industrial sites. Our approach significantly outperforms state-of-the-art baselines, yielding substantial gains in both answer accuracy and exploration efficiency.

Long-term Active Embodied Question Answering

We introduce a new task called Long-term Active Embodied Question Answering (LA-EQA), where robots must both recall past experiences and actively explore their surroundings to answer complex questions. Compared to existing active EQA and episodic EQA tasks, LA-EQA unifies these settings and extends the problem to require reasoning over multiple past episodic memories accumulated over extended periods. To the best of our knowledge, this problem is largely unexplored, and no benchmark currently exists to evaluate it.

Mind Palace Exploration

Humans use the mind palace technique to remember complex information by organizing it into a structured spatial memory, which enables efficient retrieval and traceable recall of relevant memories. We explore how this technique can be applied to long-term memory representation and reasoning in robots.

Mind Palace Exploration builds a Robotic Mind Palace that unifies past memories and environment representation (1). The Robotic Mind Palace summarizes the robot’s history of observations into multiple world instances of scene graphs. Given a question (2), the agent alternates between reasoning over the question to identify a target object (3), planning a search strategy through memory retrieval and exploration (4), and updating its working memory (5), until it is ready to answer the question (6). Additionally, we introduce early stopping criteria using the notion of Value of Information to avoid retrieving memory that is unlikely to improve the next exploration action.

Long-term Active EQA Benchmark

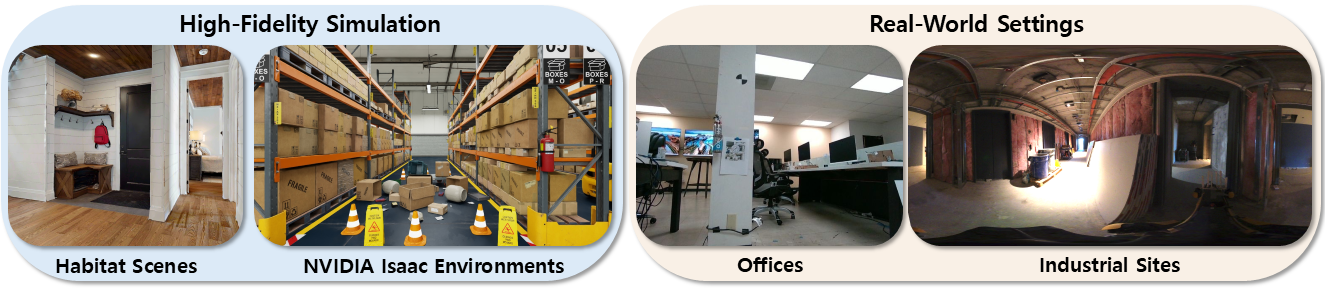

We curate the first LA-EQA dataset and benchmark, consisting of 3 simulated and 2 real-world scenes. For each simulation scene, we generate 5-10 scene variations over multiple days, reflecting changes caused by common routines. For real-world scenes, we collected 11 trajectories (30-60 mins) in an industrial site and an office environment over a 6-month period.

We categorize the questions based on their required temporal reasoning to capture different aspects of long-term scene understanding:

- Past questions pertain to a specific event observed in a single past trajectory.

- Present questions require only exploration of the current environment.

- Multi-past questions involve synthesizing information from multiple past trajectories (e.g., “What do we usually eat for breakfast?”).

- Past-present questions require reasoning over both historical memory and the current scene (e.g., “Are we missing anything we usually have for breakfast?”).

- Past-present-future questions involve predicting future outcomes based on both past and present observations (e.g., “When do you think we will run out of apples for breakfast?”).

We curated 150 questions, which uniformly cover the question types. The questions were generated by seven people to ensure the diversity of the questions.